So a week or so ago we filmed our improvised feature film in a field close to our offices. We were desperately hoping the weather would hold out, and luckily for us it just about did. Pure sunshine and barely any wind bookended the filming day itself, so it was typical that rain and wind was forecast and we’d already booked crew, cast and equipment in for that day…

This simply added to the list of challenges for recording the sound for the film. Some of which I’ll go through for you in this blog post in the hope that it may help someone out in future in similar situations.

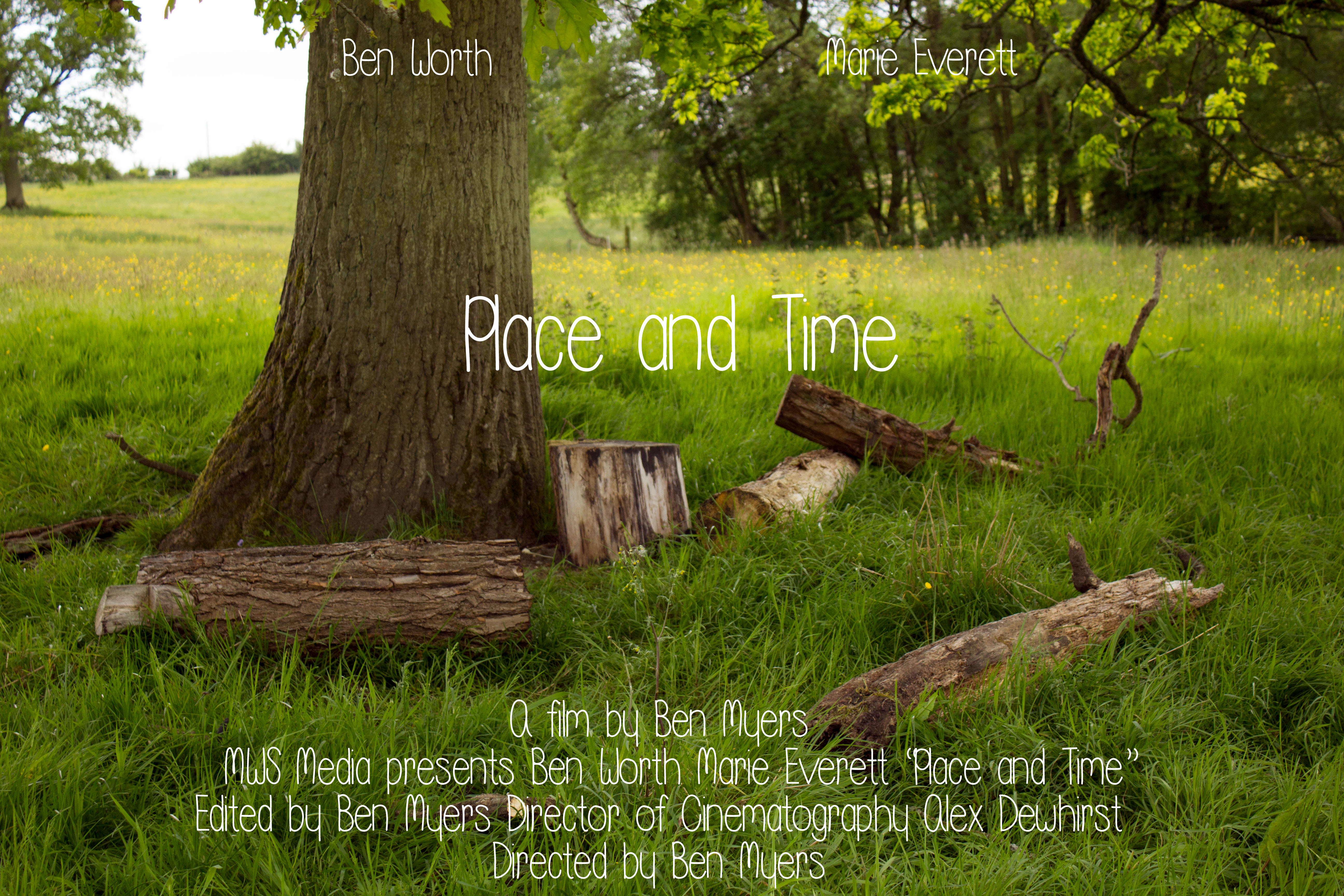

The concept for the film was an improvised feature length film, guided subtly by the director, Ben Myers, who at times was texting and calling the actors throughout the improvisation. The film features two cast members who have never met (in real life as well as the film) and who have independently developed their characters alongside the director. The premise was simply that the characters meet by finding themselves in the same field, by a tree. The idea was they would naturally speak to each other and let the conversation flow, based on how their characters would really behave towards each other in that particular situation. So for example they could have not got on well and had an argument, or they could have fallen head over heels in love, we simply wouldn’t know until the filming itself.

Coverage

So obviously our first big problem becomes coverage. How do we capture the audio without knowing what the actors are going to say, when they are going to say anything, or how loudly or quietly they are going to say something, or in which direction? It became clear from the get-go that we would have to use as many mics as possible, very well placed, as discreetly as possible, in and around the tree location itself.

There were two available sound recordists; my colleague Nick and I, who were there specifically to set up the mic placement and then monitor the recordings. Budget-wise we didn’t have very much to play with, as part of the aim of the film was to try and create something without spending too much (when is that ever not the aim?), but with little to no impact on the quality of the production either. We ended up using eight separate mics, six shotguns and a lapel mic on each actor. Out of the six shotgun mics we placed five on the ground in the grass, one pointing directly between where the two actors were advised they sit themselves, two hidden behind logs by the actors feet pointing at the opposite actor, and then two further wide side on mics, pointing directly inwards in case the actors turned the heads either left or right to speak, which inevitably happens in conversations. The sixth mic was placed in the tree above the actor’s heads. All the mics were out of shot on the wide camera, the other four camera operators knew where the mics were and simply avoided capturing them, which was easy enough as they were mainly doing close-up shots of faces.

Hiding XLR leads in the grass was also very easy thankfully (he says hoping no one will spot any in the edit itself!) and the mic dangling from a branch above the actors was severely blu-tacked and tied to the tree trunk for safety. My guess was the actors would be talented and sharp enough to say something like “Ah, a conker!” should some blu-tack fall from above them during the filming. I’m kidding of course, we made sure there was no way anything would fall down and ruin anything. We are professionals after all…

So as far as location sound recording goes, we felt we’d covered our bases in terms of what we had available to us on the day, mixed in with good mic placement. The trick was to avoid telling the actors “you must stand here, and when you speak face this way” etc. Ben really wanted them to be free to act as their characters would and within the parameters he had set them, but not feel trapped by anything technical like mics or cameras, to allow them to focus solely on performance.

Lavalier Mics

We knew shot gun mics would pose their own problems that only lapel mics might be able to get around, such as wind noise, so we decided to use two channels of our eight for attaching lavalier mics to each actor. The obvious main consideration with using lapel mics of course is visibility; how do we attach them without the cameras being able to see them? The other issue is of course noise, how do you hide a lapel mic in and around clothing but still manage to record clean sound? After some brief chats with other crew members, someone suggested we look at Rode’s “Invisilav” solution. Online videos showed that they did a very decent job of answering both our questions, so we decided to purchase a pack of three for use in the film. A mini review of the Invisilav would be as follows; they are perfect if your talent / actor is stood perfectly still, but do expect noise if they need to move around a fair bit – nothing will completely stop clothing making noise on the mics. They come with double-sided adhesive tape, which is cut to the shape of the silicone housing that holds the mic. This double-sided tape is a real pain to peel away from its backing and use, but eventually it works, just be patient when trying to peel off the backing as per the instructions. On the whole they did a very good job of making sure we had fairly clean close-miked dialogue, which for this film in particular was obviously crucial given that we had no idea what was going to be said or how close to a shotgun mic an actor would be when they spoke.

Technical Challenges

Alongside the weather and coverage, another big issue was the technical challenge of recording eight separate channels of audio, for a full hour and a half absolute minimum, in the middle of a field where there is no access to mains power. And on top of that, we have one shot, one attempt to record it and make sure it’s all captured the best it can be. The actors can obviously only meet for the first time just the once, so we had to make sure our setup was tested beforehand. One of the things the testing revealed was “What if the recorder fails as we hit stop, or the batteries die half way through and nothing is recorded?” Hhhhmmmm... It became clear that we would need to hedge our bets a bit and so we decided to split the eight mics across four different recorders, meaning that if one failed we’d still have six mic sources recorded.

We own two Tascam DR100 audio recorders. They are great for certain things but as with all portable recording equipment the main issue seems to be battery power. Ours have always been fine and never (touch wood) caused us any problems for any of our client based corporate work. But an hour and a half minimum, at the highest recording quality, powering two shotgun mics is a bit of an ask. The solution to this was to purchase external battery packs that house six AA batteries and use a USB to DC connection to power the unit, which then automatically switches itself while recording to its internal lithium battery, giving us (in theory) many hours of recording time. Testing proved this to be the case. So that’s four of the eight mics covered. The cameras used were Canon 5D’s which have no XLR mic input, however at the last minute we switched to using a Canon C100 for one camera angle, which does have XLR inputs. So it made perfect sense to use this as the recorder for the two main shotgun mics (the tree mic and the central ground mic). We then had a brainwave, whilst trying to avoid hiring kit we didn’t necessarily need; we have a Canon XF105 that also has XLR inputs and is very reliable in terms of battery use even when powering two shot gun mics for that kind of duration. So we ran the camera on the shoot, filming the crew as they filmed the actors so it could be used for “Making Of” footage, whilst also capturing the sound from the two mics placed near the actor’s feet on to the camera. Two birds, one stone I think the phrase is.

Weather

So, the Great British weather, well, it held out as I mentioned earlier which was great. Just towards the end of filming it fractionally started to spit with rain. Our plan to avoid soaking all our mics was to wrap a thin layer of cling film round each shot gun mic, then place its foam windshield over it, so that any big drops of rain soaking through the foam windshields wouldn’t actually penetrate the mic capsule and do any damage. The limitation of this was that the mic was very slightly muffled from its true recording capabilities, but it’s a compromise we had to make. If it had rained on and off throughout but not enough to make the director call cut we would have risked too much rain getting on the mics over an hour and a half and possibly doing long-term damage to the equipment.

The biggest problem was the wind, as usual. We couldn’t use big Rycote style windshields because there is no way they would’ve hidden well enough in the grass. However the grass and logs we placed the mics nearby helped out a fair bit when the wind did pick up. There was the occasional aircraft, circling overhead, which believe it or not was not within our budget to gain control over…

The Mix

It’s become clear from reviewing the audio since we filmed a few days ago that the mix itself is looking, like I thought it might, like it will be a balance between the two lapel mics and the tree and central mic mainly, occasionally dipping down the shotguns in the mix when the wind picks up or planes fly overhead. There were also some moments we hadn’t planned for that just got overlooked due to the unavailability of the location largely until the day itself, such as birds deciding to sing louder than they ever have before, and the tree mic being high up enough to act as an antenna, picking up local radio playing 80’s classics very faintly on one channel of our recording. All learning curves for the future and things we know we can get around in terms of the mix anyway. I still find that I learn something new almost every time we record something. Yes, there was inevitably noise on the lapel mics from clothing as we suspected, but some clever gating and balancing with the shotguns should be able to eradicate most of that in the mix. I’m certainly looking forward to sitting down at the computer and cracking on with it.

Conclusion

I would best describe this particular audio task as an enjoyable, challenging, scary nightmare of a recording experience. Knowing that the moment we started rolling all our options to make any changes disappeared due to the fact that we only had one chance to get it right and the work was all in the setup. In fact Nick and I were only really able to control the levels of each mic acutely throughout the filming. We had set them to medium levels in the hope that if the actors suddenly raised their voices or laughed loudly to the point where it may peak it would at least not be peaking on a mic placed elsewhere and some clever mixing would be needed at those points. Overall a big challenge that we feel we passed successfully. Bring on the edit…

Phil